You Don't Have a "Superpower"

- Deric Hollings

- Jul 5, 2025

- 14 min read

“I think of it as my superpower,” a former client once told me when discussing an undiagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) condition he believed that he had. For clarity, the American Psychological Association (APA) defines this condition thusly:

[A] behavioral syndrome characterized by the persistent presence of six or more symptoms involving (a) inattention (e.g., failure to complete tasks or listen carefully, difficulty in concentrating, distractibility) or (b) impulsivity or hyperactivity (e.g., blurting out answers; impatience; restlessness; fidgeting; difficulty in organizing work, taking turns, or staying seated; excessive talking; running about; climbing on things).

The symptoms, which impair social, academic, or occupational functioning, start to appear before the age of 7 and are observed in more than one setting. ADHD has been given a variety of names over the years, including the still commonly used attention-deficit disorder (ADD).

“Rather than conceptualizing it as a ‘superpower’ [a power or ability, such as the ability to become invisible or to fly, of the kind possessed by superheroes], could you instead think of it for what it is – a disability?” I responded to the client. Per the APA, a disability is defined thus:

[A] lasting physical or mental impairment that significantly interferes with an individual’s ability to function in one or more central life activities, such as self-care, ambulation, communication, social interaction, sexual expression, or employment. For example, an individual with low vision or blindness has a visual disability.

“No,” the client replied, “it’s a superpower.” Conceptualization of sort isn’t uncommon regarding disorders—a group of symptoms involving abnormal behaviors or physiological conditions, persistent or intense distress, or a disruption of physiological functioning.

For instance, one source states, “What I would never trade away. The positives of ADHD are numerous and mighty — creativity, empathy, and tenacity, just to name a few. Here, readers share their amazing superpowers.”

Unfortunately, “readers” sharing “superpowers” isn’t realistic. Rather, it’s quite infantilizing. It’s the kind of thing an adult says to a child when evoking specialness. Interestingly, a submission from the same source additionally (and helpfully) states:

“ADHD is not a real superpower. Claiming it is helps no one.” “In the ongoing fight to raise much-needed awareness around ADHD, it’s vital we don’t romanticize it. Pithy expressions do little to help people with ADHD when they’re called unproductive at work or disruptive in the classroom. Instead of being cute, we should be clear.”

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the appeal of delusional thinking expressed by the source. I, too, used to envision myself as having a special (super) ability to experience the world in a particular way before I received a formal diagnosis of ADHD by a Naval psychologist in 2004.

Throughout my educational process from kindergarten to graduating high school, I was frequently in trouble. I couldn’t sit still or focus, I was generally behind a level of comprehension in comparison to other students, and I was often sent to the principal’s office for discipline.

In fact, I received corporal punishment (i.e., swats, spanking, etc.) both at home and/or at school through my freshman year of high school. (I got too big to batter.) Also, adults referred to me as a “bad” child, and I self-disturbed with irrational beliefs about that label for many years.

Confusingly, I was tested for the G.A.T.E. (Gifted and Talented Education) program in either six or seventh grade, though I was promptly returned to class. Apparently, my mathematical abilities weren’t conducive to the standards of G.A.T.E.

While in high school, I took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) test and performed poorly. After graduating, I was given the opportunity to again take the ASVAB. Seemingly, I executed the task in a more suitable fashion.

My General Technical (GT) score was 105. Think of one’s GT score as correlated with an intelligence quotient (IQ) score. My slightly above average GT marker qualified me for the military occupational specialty (MOS) of military police (i.e., the cutoff score was 100).

Yet, my inferred IQ marker was just below the threshold for the MOS of military intelligence (i.e., 110). Presumably, my performance on math questions hampered me. While attending United States Marine Corps Recruit Training, I was given the opportunity to take more tests.

However, I was promptly returned to my boot camp platoon. Explaining this matter to me, I was told, “You suck at math, recruit.” Later in life, this made sense. When diagnosed with ADHD while in the military, I was also diagnosed with a “mathematics disorder.”

As a matter of context, a mathematics disorder is also referred to as dyscalculia. The APA defines this condition as “an impaired ability to perform simple arithmetic operations that results from a congenital deficit. It is a developmental condition, whereas acalculia is acquired.”

For the sake of argument, suppose that I didn’t “suck at math.” Would I have warranted the label of “giftedness?” If so, would that mean that my condition would’ve qualified as a “superpower?” First, the APA defines giftedness thusly:

[T]he state of possessing a great amount of natural ability, talent, or intelligence, which usually becomes evident at a very young age. Giftedness in intelligence is often categorized as an IQ of two standard deviations above the mean or higher (130 for most IQ tests), obtained on an individually administered IQ test.

Many schools and service organizations now use a combination of attributes as the basis for assessing giftedness, including one or more of the following: high intellectual capacity, academic achievement, demonstrable real-world achievement, creativity, task commitment, proven talent, leadership skills, and physical or athletic prowess.

The combination of several attributes, or the prominence of one primary attribute, may be regarded as a threshold for the identification of giftedness.

Given the APA definition of giftedness, I suspect that I’d qualify. (Though given how poorly written my blogposts are I question the validity of this suspicion in some regard.) Second, as not to straw-man this matter, consider what one source states about gifted children:

Creating consistent and meaningful plans for the control and management of hyperfocus will allow your Gifted and Talented children to flourish. If, and when, we look at hyperfocus as yet another superpower of our children, they will find that they are capable of much more because they are able to remain on task.

Look not at what they are missing through hyper-focusing, but look at what they are able to achieve and overcome because of it.

I argue that although likely a useful trait, giftedness isn’t a “superpower.” Of course, you may choose to disregard my perspective. Therefore, I invite you to consider what one source has to offer on this topic:

Rethinking giftedness: The dark side of “gifted” labels and “superpower” stereotypes - A personal perspective […]

As a former ‘gifted kid,’ I’ve realized that giftedness is more complex than many believe. It’s a label that often comes with its own set of challenges, expectations, and misconceptions […]

Because I was good at reading, I was expected to be equally good in all my subjects (even the things I wasn’t good at like spelling, math, and history). When I struggled, my needs were overlooked (and denied). Because I was “gifted,” I was labeled “stubborn,” “difficult,” and “lazy” for not having the “well-rounded” abilities other people expected me to have.

I relate to this outlook. Just like battery by way of belt, paddle, punches, and kicks couldn’t knock ADHD symptoms out of me; the corporal punishment which ensued on the day I told my dad that I was passed over for the G.A.T.E. program couldn’t knock traits of giftedness into me.

Even when other adults treated me as though I was gifted with artistic ability (e.g., I won art awards through middle school), or by way of leadership traits (e.g., I was considered a guiding figure among my children’s home peers), unhelpful expectations were placed on me.

Using unfavorable beliefs about my shortcomings, I self-disturbed in both childhood and adulthood. By middle adulthood, a friend of mine since high school questioned whether or not I’d considered the possibility that I may have autism. The APA defines this condition thusly:

[A] neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by markedly impaired social interactions and verbal and nonverbal communication; narrow interests; and repetitive behavior. Manifestations and features of the disorder appear before age 3 but vary greatly across children according to developmental level, language skills, and chronological age.

They may include a lack of awareness of the feelings of others, impaired ability to imitate, absence of social play, abnormal speech, abnormal nonverbal communication, and a preference for maintaining environmental sameness.

Classified in DSM–IV–TR as a pervasive developmental disorder, autism was integrated into autism spectrum disorder in DSM–5 and DSM-5-TR and is no longer considered a distinct diagnosis.

Being that in her adulthood my friend worked with special education children, having known me for decades, she expressed suspicion that I may be autistic. Although, I’ve never been assessed for this condition, let’s say for the sake of argument that I have this condition.

Would this diagnosis constitute a “superpower?” Apparently, in an interview with journalist Anderson Cooper, billionaire Bill Gates ostensibly concurred with the notion that his presumably undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder condition is “absolutely” a superpower.

Per one source, “The autistic superpower trope is infantilising, demeaning and othering and embarrassingly unrealistic. It refuses to acknowledge autistic people as fully-realised individuals with complex lives — ordinary lives encompassing the full range of human experience.”

I have no idea whether or not I’m on the autism spectrum. However, if I were, I wouldn’t maintain that I had a “superpower.” It’s a disorder, a disability. As is the case with ADHD and giftedness, there’s no logical and reasonable point of claiming that autism is a “superpower.”

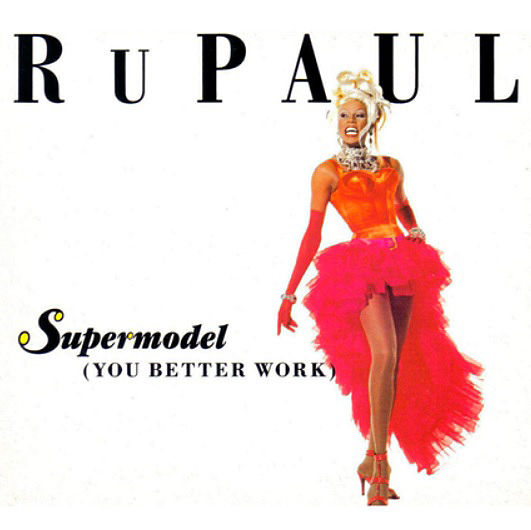

For context, the basis for writing this post was formed when recently browsing social media platforms, in particular TikTok and Reddit. On both mediums, I encountered the same graphic regarding ADHD, autism, and giftedness (admittedly modified for the current blogpost):

Photo credit (edited), photo credit (edited), fair use

I found the Venn diagram quite useful, and wanted to know more about the creator of the graphic. Unless my brief investigation yielded inaccurate results, the original image was created by Katy Higgins Lee, MFT (Marriage and Family Therapist).

Looking further into this topic, I found a video in which someone identified as Higgins Lee says, “I also wanted to create a resource that describes all of these in neutral language, instead of using either deficit-based language, or like, ‘superpower’ terminology, ‘cause both are problematic.”

I appreciate this perspective. ADHD, autism, giftedness, and other conditions, disorders, disabilities, etc. aren’t superpowers. Notably, in the Higgins Lee video, she mentions another video by “Dr. Joey” who offered a similar outlook by stating:

There’s different ways that you can look at ADHD and autism, but still they’re generally seen to be disabilities. The word disorder is a little bit more contentious [even though autism spectrum disorder is literally the name of the diagnosis], um, but generally speaking, ADHD and autism – by most people – aren’t viewed as, like, a ‘superpower’ or an exceptionality or something that makes you stand out above the rest, as opposed to giftedness.

So what’s going on with giftedness is there’s an inherent, uh, exceptionality to that […] It’s like they have…they have a gift. They have something exceptional that they can do that is unique, um, to them. Giftedness is tricky, because it can’t really be easily quantified.

Dr. Joey went on to discuss how giftedness tends to relate to a specific area, such as one who is gifted in math (of which I’m undoubtedly excluded). One imagines that there are many people in certain walks of life who are gifted in athleticism, and who may not be particularly intelligent.

For example, being able to excel in the National Basketball Association (NBA) may not require a high IQ. Yet, I don’t question whether or not these professionals are gifted. All the same, they don’t have “superpowers” (though one wonders how Stephen Curry is able to do what he does).

Of course, this isn’t meant to infer that NBA players aren’t intelligent. I was a Marine, for crying out loud. In a blogpost entitled Spaz on That Ass, I stated:

Due to inter-service rivalry, there’s a derogatory joke referencing the supposed low intelligence of Marines which is often used by airmen, sailors, and soldiers. (I’d include coasties, but let’s not be silly.)

The joke states that Marines eat crayons. As one person clarifies, “It is not politically correct these days but autistic and retarded kids eat crayons. Therefore Marines are autistic retarded [k]ids.”

A version of this gag also results when someone says, “I have neither the time nor the crayons to explain this to you.” As one person expands, “It’s basically saying you’re stupid and I don’t have crayons to draw out what I’m trying to say to your infantile mind. And even if I had the crayons I don’t have the time to draw it out.”

In closing, you don’t have a “superpower,” because you’re little more than a fallible human being. No diagnosis of ADHD, autism, or otherwise will change this fact. Likewise, no label of giftedness or otherwise will alter truthful information that I’ve expressed herein.

If you, like me, have ADHD or other diagnoses (of which I do), then I invite you to practice unconditional self-acceptance regarding your disordered disability. However, infantilizing positive psychology mumbo-jumbo isn’t necessary in regard to your condition.

You aren’t a superhero, and neither am I. So how about taking off your ridiculous cape, learning to work with whatever it is you have, and letting go of childish notions about how special you think you are? Genuinely, you don’t have a “superpower.”

If you’re looking for a provider who tries to work to help understand how thinking impacts physical, mental, emotional, and behavioral elements of your life—helping you to sharpen your critical thinking skills, I invite you to reach out today by using the contact widget on my website.

As a psychotherapist, I’m pleased to try to help people with an assortment of issues ranging from anger (hostility, rage, and aggression) to relational issues, adjustment matters, trauma experience, justice involvement, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety and depression, and other mood or personality-related matters.

At Hollings Therapy, LLC, serving all of Texas, I aim to treat clients with dignity and respect while offering a multi-lensed approach to the practice of psychotherapy and life coaching. My mission includes: Prioritizing the cognitive and emotive needs of clients, an overall reduction in client suffering, and supporting sustainable growth for the clients I serve. Rather than simply trying to help you to feel better, I want to try to help you get better!

Deric Hollings, LPC, LCSW

References:

ADDitude. (2025, January 14). What I would never trade away. Retrieved from https://www.additudemag.com/slideshows/positives-of-adhd/

American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2018, April 19). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/attention-deficithyperactivity-disorder

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2023, November 15). Autism. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/autism

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2023, November 15). Disability. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/disability

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2018, April 19). Disorder. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/disorder

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2018, April 19). Dyscalculia. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/dyscalculia

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2018, April 19). Giftedness. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/giftedness

CNN. (2025, February 5). Bill Gates reveals why he’s probably on the autism spectrum [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/QxcdxON0rb4?si=qvG0YKk9dD0Gr4ys

Explore More Gifted. (2021, August 31). The superpower of hyperfocus. Covington Latin School. Retrieved from https://exploremoregifted.org/f/the-superpower-of-hyperfocus

Gaudry, S. (n.d.). Why are there so many jokes about Marines eating crayons? Quora. Retrieved from https://www.quora.com/Why-are-there-so-many-jokes-about-Marines-eating-crayons

Higgins Lee, K. (n.d.). Giftedness, autism, ADHD Venn diagram PDF (Free download) [Image]. Trending Paths. Retrieved from https://www.katyhigginslee.com/giftedness-autism-adhd-venn-diagram-pdf-free-download

Higgins Lee, K. (n.d.). Katy Higgins Lee, MFT [Official website]. Trending Paths. Retrieved from https://www.katyhigginslee.com/

Higgins Lee, K. (2024, January 15). Trending Paths [Official TikTok account] [Video]. TikTok. Retrieved from https://www.tiktok.com/@tendingpaths/video/7324491286705163551

Hollings, A. (2022, January 14). Do Marines really eat crayons? Only the red ones. Sandboxx. Retrieved from https://www.sandboxx.us/blog/do-marines-really-eat-crayons-only-the-red-ones/

Hollings, D. (2024, July 6). Addressing misconceptions with clients. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/addressing-misconceptions-with-clients

Hollings, D. (2023, April 22). Control. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/control

Hollings, D. (2024, June 3). Daily self-care. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/daily-self-care

Hollings, D. (2024, January 7). Delusion. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/delusion

Hollings, D. (2022, March 15). Disclaimer. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/disclaimer

Hollings, D. (2025, March 12). Distress vs. disturbance. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/distress-vs-disturbance

Hollings, D. (2025, March 9). Factual and counterfactual beliefs. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/factual-and-counterfactual-beliefs

Hollings, D. (2023, September 8). Fair use. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/fair-use

Hollings, D. (2024, May 11). Fallible human being. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/fallible-human-being

Hollings, D. (2024, May 17). Feeling better vs. getting better. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/feeling-better-vs-getting-better-1

Hollings, D. (2025, March 5). Five major characteristics of four major irrational beliefs. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/five-major-characteristics-of-four-major-irrational-beliefs

Hollings, D. (2023, October 12). Get better. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/get-better

Hollings, D. (n.d.). Hollings Therapy, LLC [Official website]. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/

Hollings, D. (2024, January 2). Interests and goals. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/interests-and-goals

Hollings, D. (2022, November 10). Labeling. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/labeling

Hollings, D. (2025, January 14). Level of functioning and quality of life. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/level-of-functioning-and-quality-of-life

Hollings, D. (2023, September 19). Life coaching. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/life-coaching

Hollings, D. (2023, January 8). Logic and reason. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/logic-and-reason

Hollings, D. (2022, June 23). Meaningful purpose. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/meaningful-purpose

Hollings, D. (2024, June 2). Nonadaptive behavior. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/nonadaptive-behavior

Hollings, D. (2024, January 9). Normal vs. healthy. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/normal-vs-healthy

Hollings, D. (2022, October 22). On empathy. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/on-empathy

Hollings, D. (2023, September 3). On feelings. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/on-feelings

Hollings, D. (2023, April 24). On truth. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/on-truth

Hollings, D. (2024, May 17). Open, honest, and vulnerable communication. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/open-honest-and-vulnerable-communication

Hollings, D. (2025, April 25). Preferences vs. expectations. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/preferences-vs-expectations

Hollings, D. (2024, May 5). Psychotherapist. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/psychotherapist

Hollings, D. (2025, June 14). Pulled like a puppet by every impulse. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/pulled-like-a-puppet-by-every-impulse

Hollings, D. (2024, July 10). Recommendatory should beliefs. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/recommendatory-should-beliefs

Hollings, D. (2024, January 20). Reliability vs. validity. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/reliability-vs-validity

Hollings, D. (2025, June 15). Retarded. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/retarded

Hollings, D. (2022, November 1). Self-disturbance. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/self-disturbance

Hollings, D. (2024, March 24). Smartphone and social media addiction. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/smartphone-and-social-media-addiction

Hollings, D. (2022, August 1). Spaz on that ass. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/spaz-on-that-ass

Hollings, D. (2023, October 16). Straw man. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/straw-man

Hollings, D. (2024, February 27). Suffering, struggling, and battling vs. experiencing. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/suffering-struggling-and-battling-vs-experiencing

Hollings, D. (2025, February 28). To try is my goal. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/to-try-is-my-goal

Hollings, D. (2024, June 19). Treatment vs. management. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/treatment-vs-management

Hollings, D. (2023, March 1). Unconditional self-acceptance. Hollings Therapy, LLC. Retrieved from https://www.hollingstherapy.com/post/unconditional-self-acceptance

Jae L. (2024, April 4). The problem with talking about autistic superpowers. Medium. Retrieved from https://jael999.medium.com/the-problem-with-talking-about-autistic-superpowers-c34a9ee4a0e7

Jones, L. (n.d.). Why do people say Marines eat crayons? (Explained!). Mangful. Retrieved from https://mangoful.com/why-people-say-marines-eat-crayons/

Kincella, M. T. (2025, May 9). “ADHD is not a real superpower. Claiming it is helps no one.” ADDitude. Retrieved from https://www.additudemag.com/adhd-superpowers-romanticizing-disorder/

Luis_molinero. (n.d.). Happy person hilarious hero eyes [Image]. Freepik. Retrieved from https://www.freepik.com/free-photo/happy-person-hilarious-hero-eyes_1151379.htm#fromView=search&page=1&position=17&uuid=b0b29197-bc7a-4f4b-9f63-93f331c5717b&query=superhero

Nd_psych. (2024, March 10). Replying to @InspectorTalon autism adhd and giftedness [Video]. TikTok. Retrieved from https://www.tiktok.com/@nd_psych/video/7344863074035322130

NeuroDivergent Rebel. (2024, July 12). Rethinking giftedness: The dark side of “gifted” labels and “superpower” stereotypes - A personal perspective. Substack. Retrieved from https://neurodivergentrebel.substack.com/p/rethinking-giftedness-the-dark-side

NewBliss. (2015). Can somebody please explain the joke “I have neither the time or the crayons to explain this to you” please? Reddit. Retrieved from https://www.reddit.com/r/OutOfTheLoop/comments/3qeofq/can_somebody_please_explain_the_joke_i_have/

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Anderson Cooper. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anderson_Cooper

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Bill Gates. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Gates

Wikipedia. (n.d.). DSM-5. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DSM-5

Wikipedia. (n.d.). List of mental disorders in the DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_mental_disorders_in_the_DSM-IV_and_DSM-IV-TR

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Positive psychology. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positive_psychology

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Stephen Curry. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Curry

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Venn diagram. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venn_diagram#:~:text=A%20Venn%20diagram%2C%20also%20called,not%20in%20the%20set%20S.

Comments